On Watching Lain & Being Trans in 2022, or, How Digital Violets Bloom

Note: This piece contains spoilers for the plot content of Serial Experiments Lain. While I strongly believe that knowing the ending of the plot of Serial Experiments Lain does not diminish the value of watching it, I have included this warning for those who wish to experience the work prior to reading this piece.

I first watched Serial Experiments Lain in the early months of 2022. Lain is about many things to many people – dissociative identity disorder, loneliness in a crowd, a prediction of the way internet addiction would fuel isolation in the 2010s. But the show also has a sizable transgender fanbase, perhaps because it's easy to read transness into Lain's character.

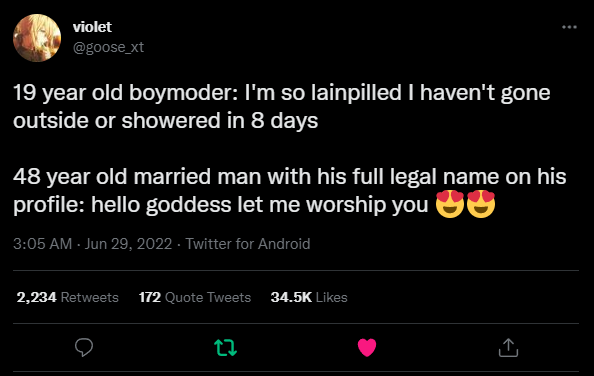

If you're transgender and of a certain age, you probably either are or have been closeted offline and only been transgender online. Offline, your voice, face, shoulders, your chest, your body, are so visible and so largely formed without your consent. They are barriers for many trans people of all genders. Trans people often have such complicated relationships with what we look like and the effects of our dysphoria on our mood and motivation in the physical space that it's a meme that trans women in particular keep messy rooms and barely take care of ourselves physically, which itself is associated with Serial Experiments Lain.

Offline, my body makes me nervous to ask people to use she/her pronouns. Online, I have more control. On Discord, I look like Fuuka Yamagishi from Persona 4 Arena. I've been Rona from Swan Boy. On Tower Unite, I'm Chihiro Fujisaki from Danganronpa. In online spaces, I look as cute as I want to in real life without needing to put constant effort into the anxieties of looking femme enough. Of if my body will betray me to strangers. Even my voice is carefully managed online. The voice people hear online can be modified by the same voice training techniques trans people learn offline, but it can also be intercepted and changed by software, spoken by a robot on my behalf, or rendered completely inaudible: words on a screen that sound however you imagine them to. When you're trans, it's likely that for some period of time in your life, the you that people know, see, hear, even touch, smell, or taste offline is a persona you've put on for your own physical and emotional safety. It's not authentic, or not as authentic as the person you get to choose to be in online spaces. For many trans people, the online self is the real self, and our bodies are the subject of intensely complicated relationships that may or may not ever be fully resolved; comfortable; true.

Lain, too, is disconnected from her physical self. She spends most of her time in her room, connected to the Wired. Her room is a mess of connected boxes that make her computer more powerful. The floor is flooded. She's barely taking care of her physical space, let alone her physical body.

She is surprised by the alternative version of herself that she sees online, a self that is more confident, more feminine. She's even scared of it. As she grows more comfortable with this alternate self, however, she also recognizes that the Wired, the world of the online, is not a fully separate world from the one her body inhabits. In fact, the lines between the two worlds are becoming increasingly blurred as time goes on. And if the two worlds are the same, it's difficult for there to be two entirely separate Lains. In the end, Lain accepts her online self as true. For her, this means losing everyone she has loved, discarding the existence of her corporeal form, and realizing that nobody else seems to know who she is. Many trans people leave behind our old bodies, making changes with hormones and surgeries to become who we really are and who we are online. Many leave behind old identities, refer to our given names as dead, and take on names of our own. Many talk about how we feel like our pre-transition life was being lived by a different person. Many experience that other people feel like we've 'changed' and they don't know who we are anymore. Too, too many of us lose our loved ones because of bigotry or our own fear of the stress and danger of coming out, again and again, over and over. The connections between Lain and trans people are real, and felt. The identity exploration of the Wired as Lain comes to find herself mirrors a trans online experience. Here's just a small example from my own life.

Like many people, the COVID-19 pandemic brought my life entirely online. There was no physical workspace anymore. I taught online. I studied online. I worked online. I ordered food online. I likely spent no more than an hour or two a day away from my room. From my bed. From my computer. My friends at the time were busy managing their own reactions to the pandemic. Some became reclusive. Some threw themselves entirely into their work. Some were semi-social online, but only on social media platforms and only for a little bit a day, probably tired of how much time they were spending on the computer. None of these relationships were maintained. It's not that I've lost those friendships, but their character is different now. In the best cases, we're reestablishing a connection that had been lost for two years. In the worst cases, I've seen them at an event and we've briefly acknowledged each other, afraid to confront the awkwardness of going from speaking weekly or even daily in-person to exchanges of three or fewer text messages a month. Semi-annually. Not at all. Instead, all of my relationships became exclusively online, either with internet friends from pre-pandemic or, for the overwhelming majority of my current close relationships, formed online from 2020-2022.

The locus of these relationships is the kind of group that only exists online – a discord server that exists as a spinoff of a different, now dead discord server that itself existed as a fan community for a mildly popular Let's Play group that disbanded years ago but still maintains about 25 active posters. I don't remember if I had been using my handle, TheRecognitionScene (taken from the best Mountain Goats song) before I joined that server, or if I changed my handle just before jumping in. In time though, we were unconsciously workshopping nicknames. I've been called Recognition, Scene, TRS, Recog, even THScene as a weed pun, after briefly jokingly changing my handle to TheHeccognitionScene. The one that stuck, however, was Rec. A snappy, short, ungendered name. I liked the lack of gendering. At the time, I was identifying solely as nonbinary, and I was solely using the name given to me at birth – a name I had learned was, technically, gender neutral but was, practically, roughly 98% male. I was latched onto that technical gender neutrality. I figured that no matter where my gender journey ended, I wouldn't change my name. It was good enough, and it was what I was used to everyone calling me. At least, it was what everyone had been calling me up until then.

Online, in my main community, I was consistently referred to as Rec both in text and voice chats. When I branched out into other communities, the nickname workshop would start up again, but was truncated by, "I'm used to being called Rec at this point." There was no reason to go out into the world of people who would call me by my birth name, so for hours a day, literally thousands of hours over the course of years, if someone was talking about me or trying to get my attention, hearing "Rec" was my cue. When you hear something that much, it becomes a reflex. I'd guess it's the same mechanism by which we come to feel the association of ourselves to our names given at birth. One day, I was briefly talking to myself in the kitchen, and called myself Rec, instead of my given name. This was a moment of revelation. The prolonged detachment from use of my given name, along with the reflexive attachment of myself to this new name that I had taken, deprogrammed my relationship to my given name. It provided a space that allowed me to ask if I actually felt a genuine connection to my name, or if I had begrudgingly accepted it. If I just thought it was easier than trying to find a new name. If it was just something that was 'good enough.' And I realized that was true. I didn't care for my 'real' name, and maybe never had.

This story could continue with an examination of the actual process of finding the non-Rec name I ultimately took, but it doesn't. The important thing isn't that process, but where it happened. It happened online, a world where a person can present themselves as anything they want to be. There is plenty of concern around catfishing and other forms of lying and misidentifying, worries that anyone can say or be anything on the internet. But when I saw Lain in 2022, increasingly aware that I was less strictly nonbinary and more girl (but still kind of nonbinary -- Nat Puff, a singer and Vine star, once described this sort of identity as being like how "a non-dairy vegan cheese both is & isn't cheese"), I connected with Lain. I connected because we both knew the real power of the internet. Given the opportunity to be absolutely anything, for the first time in my life, I chose to be me.

This article was created by Violet